Inicio del mensaje reenviado:

Resumen: no funcionan ni como preventivos ni en la enfermedad leve. En la DMAE moderada o avanzada previenen su progresión.El consumo de vegetales y luteína y zeaxanthina se asociaron a reducción de riesgo de DMAE

.'Eye Health' Supplements: Do the Benefits Justify the Cost?

Should I take those "eye vitamins"?

Do carrots really make my eyesight better?

What can I eat to prevent macular degeneration?Such questions are common in the primary care setting. Flooded with an array of supplements at any pharmacy or grocery store, patients are justified in wondering which supplements might benefit their ocular health—or if any supplementation is needed at all. In most cases, the answer is far from straightforward, but supplements represent a modifiable risk factor in ocular conditions that often have a genetic component. To help clinicians guide patients, this article provides a practical overview on three of the most common ocular conditions for which supplements and dietary factors may play a role.

Macular Degeneration

The Trials

The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS)[1] and the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2)[2] are two of the largest and most rigorous clinical trials that have investigated the effects of nutritional supplementation on the progression of dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD) to wet AMD. Observational trials also have assessed the impact of diet and supplements on the development and progression of AMD[3-5].

The Results

Patients without AMD did not benefit from taking the AREDS formulation.[1]

Patients with mild or borderline AMD did not benefit from taking either the AREDS or AREDS2 formulation.[1]

Both the AREDS and AREDS2 formulations slightly lowered the risk for AMD progression in those patients with intermediate or advanced AMD.[1,2]

Patients who smoke should take the AREDS2 formulation to avoid the beta-carotene in the AREDS formulation, which can increase the risk for lung cancer.[2]

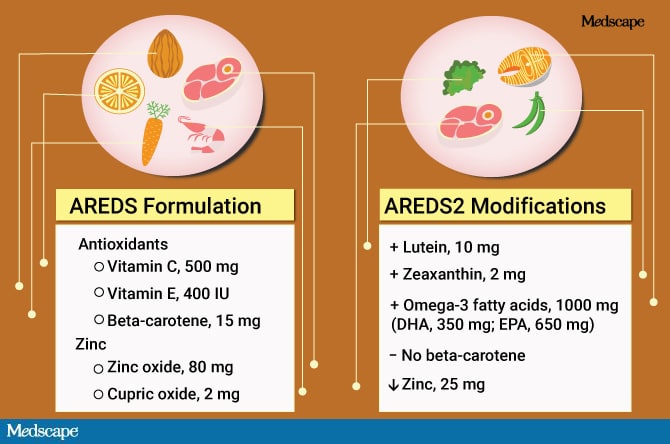

Lutein, zeaxanthin, and omega-3 fatty acids were included in the AREDS2 formulation but did not decrease the risk for AMD progression (Figure).[2]

The Blue Mountains Eye Study[6] found that the consumption of vegetables and dietary lutein and zeaxanthin was associated with a reduced risk for AMD.

Figure. Formulation and modifications of AREDS and AREDS2

The Conversation

Patients with intermediate or advanced AMD should be encouraged to take the AREDS or AREDS2 formulation as a nutritional supplement.

Smoking is a risk factor for the development and progression of AMD and should be discouraged.

Physical activity should be encouraged, as it has been demonstrated to have a modest protective effect.

A diet consisting of fish, fruits, leafy greens, and nuts has been shown to be beneficial in some studies.

Cataracts

The Trials

AREDS also addressed the benefits of antioxidants on cataracts but in an observational rather than an interventional way.[7] The cross-sectional Blue Mountains Eye Study investigated the relationship between cataracts and supplements via a patient questionnaire.[8] The Physicians' Health Study was a longitudinal study that also assessed the relationship between cataracts and supplements.[9] The Beaver Dam Eye Study reported on the relationship between the 5-year incidence of cataracts and supplements.[10]

The Results

One observational trial that included only women identified a healthy diet as being associated with a lower risk for cataract development[11]

Lutein, zeaxanthin, and B vitamins may decrease the risk for cataracts.[7,12]

Large, randomized trials found no benefit to taking vitamins C and E, beta-carotene, or selenium.[13,14]

The results are mixed regarding the potential benefit of a multivitamin.[9]

Sunlight exposure likely plays a role in the pathogenesis of cataracts, although knowledge of their exact pathogenesis is not fully understood.[15]

The Conversation

Cataract surgery is the only treatment for cataracts.

No therapy has been proven to prevent or slow the progression of cataracts.

Wearing sunglasses may protect against ultraviolet light exposure that can damage the lens.

Recommending a multivitamin is probably appropriate, as it may be beneficial and is without adverse effects.

Smoking increases the risk of developing cataracts, and patients who smoke should be encouraged to quit.

Controlling systemic conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension, may not directly impact the development of cataracts but does help make patients better surgical candidates.

Dry Eye Disease

The Trials

The Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society International Dry Eye Workshop II (TFOS DEWS II) is a collaboration of 150 dry eye experts from 23 different countries that analyzed thousands of articles on dry eye disease to generate the comprehensive report, which provides the latest summary on the definition, classification, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and impact of dry eye disease, in addition to providing evidence-based clinical recommendations.[16] An abundance of trials focus on dry eye disease, but TFOS DEWS II provides the most robust summary of the available evidence.

Completed after the publication of TFOS DEWS II, the Dry Eye Assessment and Management Study (DREAM) investigated the impact of omega-3 on the signs and symptoms of dry eye.[17]

The Results

Systemic dehydration may contribute to the severity of dry eye by increasing tear osmolarity.[16]

Altering certain environmental factors (eg, humidity) can impact dry eye disease.[16]

In DREAM, omega-3 supplements were no better than the placebo olive oil in decreasing the signs and symptoms of dry eye.[17] Other trials investigating essential fatty acids have been too short to establish a consensus.

Antioxidant supplementation has shown some promise in the treatment of dry eye, but the trials have been relatively brief.[16]

The Conversation

Dry eye disease is often multifactorial, and determining whether supplements are helpful is difficult.

Increasing hydration is a simple modification that may decrease symptoms.

The use of omega-3 supplements may have benefits, but trial results have been mixed.

Increasing humidity is an easy intervention that may increase ocular comfort.

Alcohol consumption may worsen the signs and symptoms of dry eye.[18].

A Simple Strategy Is Often Best

While the evidence on many supplements is limited and conflicting, it is clear that no superfood prevents the development of such ocular conditions as AMD, cataracts, and dry eye disease. Until more rigorous evidence is available, sometimes the simplest strategies are the best. Eat healthy foods, wear sunglasses, drink water, and avoid smoking—these straightforward lifestyle modifications are recommended nearly ubiquitously in healthcare, and should continue to be, as there is evidence to support them.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

References

Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417-1436. Abstract

Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research Group. Lutein+zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids for age-related macular degeneration: the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:2005-2015. Abstract

van Leeuwen R, Boekhoorn S, Vingerling JR, et al. Dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of age-related macular degeneration. JAMA. 2005;294:3101-3107. Abstract

Mares JA, Voland RP, Sondel SA, et al. Healthy lifestyles related to subsequent prevalence of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:470-480. Abstract

Seddon JM, Ajani UA, Sperduto RD, et al. Dietary carotenoids, vitamins A, C, and E, and advanced age-related macular degeneration. JAMA. 1994;272:1413-1420. Abstract

Tan JS, Wang JJ, Flood V, et al. Dietary antioxidants and the long-term incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:334-341. Abstract

Glaser TS, Doss LE, Shih G, et al. The association of dietary lutein plus zeaxanthin and B vitamins with cataracts in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study: AREDS report No. 37. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1471-1479. Abstract

Cumming RG, Mitchell P, Smith W. Diet and Cataract: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:450-456. Abstract

Christen WG, Glynn RJ, Manson JE, et al. Effects of multivitamin supplement on cataract and age-related macular degeneration in a randomized trial of male physicians. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:525-534. Abstract

Lyle BJ, Mares-Perlman JA, Klein B, Klein R, Greger JL. Antioxidant intake and risk of incident age-related nuclear cataracts in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:801-809. Abstract

Mares JA, Voland R, Adler R, et al. Healthy diets and the subsequent prevalence of nuclear cataract in women. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:738-749. Abstract

Moeller SM, Voland R, Tinker L, et al. Associations between age-related nuclear cataract and lutein and zeaxanthin in the diet and serum in the Carotenoids in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study, an Ancillary Study of the Women's Health Initiative. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:354-364. Abstract

Matthew MC, Ervin AM, Tao J, Davis RM. Antioxidant supplementation for preventing and slowing the progression of age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Jun 13;(6):CD004567.

Christen WG, Glynn RJ, Gaziano JM, et al. Age-related cataract in men in the selenium and vitamin E cancer prevention endpoints study: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:17-24. Abstract

West SK, Duncan DD, Munoz B, et al. Sunlight exposure and risk of lens opacities in a population-based study: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation project. JAMA. 1998;280:714-718. Abstract

Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, et al. TFOS DEWS II Management and Therapy Report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:575-628. Abstract

The Dry Eye Assessment and Management Study Research Group. n-3 fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of dry eye disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1681-1690. Abstract

Kim JH, Kim JH, Nam WH, et al. Oral alcohol administration disturbs tear film and ocular surface. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:965-971. Abstract

Medscape Ophthalmology © 2018 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this article: 'Eye Health' Supplements: Do the Benefits Justify the Cost? - Medscape - Oct 24, 2018.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario

Danos tu opinion, enriquece el post.